We’ve all said or done hurtful things either by accident or intentionally. If we’re in a relationship long enough, it’s bound to happen. The injury can happen for many reasons. Sometimes we feel hurt so we hurt back. Sometimes we’re carrying around so much hurt from past relationships that we act from a defensive (or offensive) place. Sometimes we expect to be hurt, so we hurt first.

After we’ve hurt someone we love so many feelings are likely to surface. We might experience guilt, shame, residual anger at the other person, anger at ourselves, and sadness. We want to apologize for our actions, but we don’t know how or where to start. And the difficulty of extending an apology is exacerbated by our anger at the other person if we feel hurt by them, too. It’s pretty common to succumb to the temptation of sweeping it under the rug and forgetting about it (until the next time).

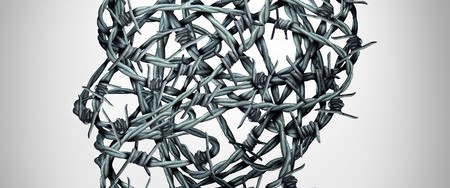

And while it is easier to forget about it in the short term, this is a dicey way to go. When we don’t hold ourselves accountable for wrongdoing, we send messages to our loved ones that we aren’t prioritizing their feelings, that dealing with conflict is too scary, that we aren’t concerned with their experience, and that we have difficulty with interconnectedness. Withholding an apology is a way to cut off intimacy and garner fear and resentment in the relationship, things that, over time, can kill a relationship. Most of us let this happen unintentionally. We’re not necessarily trying to sabotage the relationship (at least not consciously).

So, how can we do our part to keep this from happening? We have to show our loved one empathy and take responsibility. This starts with getting ourselves back on track. We have to remind ourselves what our values are and the importance of the relationship. This will help us stay in integrity with ourselves when we start the conversation and maintain our resolve when it starts to feel uncomfortable (because it will).

Once we’ve grounded ourselves in our values and our commitment to our loved one, we can come to them in an attempt to make peace. Sometimes we come to them, and they’re not ready to talk about it. That’s ok. This process is not about absolving ourselves of anything; it’s about showing integrity and love to the other person. It’s important to give respect and wait until they’re ready.

When they are ready to start the conversation, we should begin by taking responsibility for whatever it is we did or said. The most important thing is not that we start off by effusively apologizing; that indicates that our primary goal is to be forgiven, that this whole process is about making ourselves feel better. The most important thing is to let the person know we see them, that we understand what we did wrong, and that we want to know how they experienced the hurt. So we listen.

Next, we validate them. We listen to them, and we validate their experience. We make room for them as they communicate how they feel about what happened. This is not the time for us to defend ourselves or to explain our actions. This is the time for us to listen to the other person’s experience.

Finally, we show empathy. We let the other person know that we can understand how they might be feeling. If this understanding eludes us, we can ask supportive questions to help us identify with them.

Ok, so we take responsibility, listen, validate, show empathy. There is a time in the conversation to explain what was happening for us, and it’s now. After we’ve taken responsibility, listened, validated, and shown empathy, we can communicate our experience.

It’s a little tough-going at first, but this process is incredibly rewarding. It nurtures the relationship. If you have any questions or need some clarification, please let me know.

Love and Be Loved,

Natalie