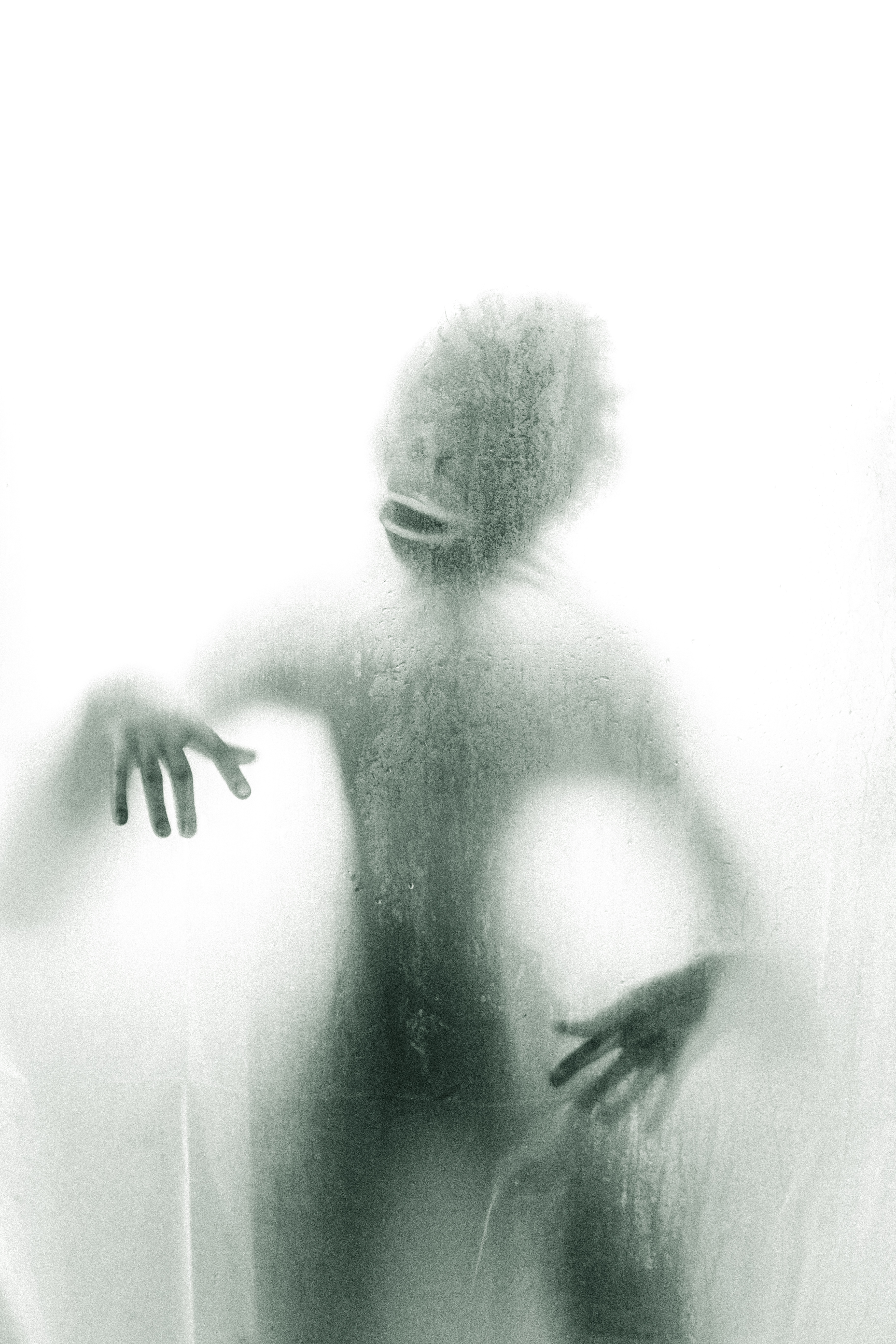

As a species, we’re in for some challenges. Humans have both nervous systems and self-awareness, the awareness of change, loss, and of death. We are aware that situations change and it motivates us to hold onto the situations we like and try to force a shift in situations we don’t like. We’re aware of loss so; we go to great lengths in trying to avoid it. We’re aware of death and generally fear it so, we engage in all sorts of behaviors and thinking in an attempt to gain control over it. Since everything is temporary, all of our grasping and holding and forcing and avoiding is useless. There is no lasting way for us to ever really hold onto something or someone, force a shift, or avoid change, loss, or death. And this creates a pretty uneasy sense of being.

Look at some of your own fear-based beliefs for a second. What makes you nervous? What are you believing when you notice the nervousness? What do you dread? What are you believing when you notice the dread?

We have an extensive list of strategies that we employ to avoid feeling the discomfort of these beliefs, to avoid feeling our fear of life’s fluidity. We numb. We fight ourselves or others. We seek comfort in addiction.

Underneath all of this struggle is the fear that we are not ok.

In the mythology of the Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama’s final challenge before he reached enlightenment was doubt. Mara, the dark deity symbol of humanity’s shadow side, our challenging emotions, appeared to Siddhartha in the form many distractions some of which were fear, pain, and lust. Finally, Mara appeared to him as doubt. Siddhartha experienced the most difficulty and discomfort with this last challenge. Siddhartha put his hand to the ground and felt the earth, calling upon it to ground him and give him strength. He looked up at Mara and said, “I see you, Mara. Come, let’s have tea.”

I’m always struck by this story. I find it comforting that Siddhartha, someone who had practiced for years, received years of mentoring and training and support, someone who was so well-resourced still felt the challenge of Mara, of the hard-to-feel, painful human emotions. I also appreciate that working through his last challenge involved asking for help, that he didn’t try to do it alone. And to boot, he invited the damn thing to tea!!

Siddhartha didn’t gain freedom from Mara all at once. It took years of practice and training. Gradually, after reaching out for help and engaging his own presence, he extricated himself. He was free.

On this quest for our own freedom, we learn of at least two important resources available to us as suggested by the Buddha mythology: 1) to ask for help when dealing with a challenge and 2) to be present with our experience of our process.

It’s so hard to keep ourselves from being swept away by the runaway train of our limiting beliefs, beliefs about ourselves and others, about the nature of the world; our fears of unworthiness; our doubt of our own lovability. Sometimes we can see this train coming for us and we freeze, unable to fight it. Sometimes we don’t see it coming; we realize we’re on it and don’t know how it happened. Sometimes we try to outrun it or fight it. One way or another, it picks us up anyway. Most of us are familiar with this cycle. Most of us know exactly what it’s like to be caught in Mara’s grip and to feel utterly helpless.

Asking for help is hard enough. Sitting with the discomfort, bringing presence to it is even more challenging. It requires a willing attentiveness, a moment of pause, and gentle inquiry. The sheer thought of asking ourselves gentle, inquiring questions when we’re in the middle of some kind of freak out brings with it its own uncomfortable trials.

Something I’ve found helpful both personally and professionally is Byron Katie’s work. It is aptly named “The Work.” She gives us four questions to pose to ourselves when we are facing the underlying doubt of our ok-ness. In those moments, Katie recommends that we ask ourselves:

- Is it true? We know that the experience of the belief feels real, but is the belief true?

- Can you absolutely know that it’s true? What is the indisputable evidence?

- How do you react, what happens, when you believe that thought? What happens for you? What is it like for you? What is the impact of this thought or belief on you? On others?

- Who would you be without the thought? Can you sense what life would be like, what you would be like if you no longer lived your life by this thought or belief?

These four questions get us off to a good start in dismantling maladaptive or limiting thoughts and beliefs, thoughts and beliefs that served us at one time in our lives, but that are now crippling us. If you find it difficult to ask yourself these questions, start with this one: Am I willing to pay attention to what this experience is like for me? We can’t always jump right in so, simply bringing the intention of presence if often a good place to start.

I recommend first trying these investigative questions with a shallow or midlevel fear-based belief. Since we are often floating around in the experience of these thoughts and beliefs, identified with them, bringing attention and presence can be really intense. Start slow. If you’d like to apply this approach to deeper fears and beliefs including trauma, I recommend doing so with the help and support of a therapist or healer.

Love and Be Loved,

Natalie